The title of today’s post makes it obvious that this might be a controversial topic. Writers pursuing traditional publishing are often told not to pay for editing before submitting to agents or publishers. But is that always the best advice?

The “rule” originated because in the days before valid self-publishing options, there were too many willing to take advantage of authors. (Er, there still are too many willing to take advantage of authors, but let’s stick to this one point. *smile*)

Pre-published authors were bombarded with claims: “Pay me to edit your work, and I guarantee you’ll get an agent/publisher.” Er, no. No one can guarantee a result of an agent or publisher unless they’re in cahoots, which some of these scammers were (and are).

Also back then, many editors were employees of a publisher, rather than a freelance contractor, unlike how they are now. That meant there weren’t many quality editors able to freelance for anyone and everyone.

Put that scam aspect together with the fact that there weren’t other legitimate editing or publishing options years ago and the advice to not pay for editing before submitting made sense. Any editors we found as pre-published “nobodies” were likely to be scammers or unqualified.

But the landscape has changed just as much as the post-apocalyptic settings in some of our stories. We’ve had to change our opinions and attitudes about many old-school advice “rules,” and today Sharon Hughson, a pre-published author who’s pursuing traditional publishing, is here to talk about whether this advice about editing should be next on the chopping block. Please welcome, Sharon Hughson! *smile*

*****

How a Professional Edit

Can Outshine other Forms of Feedback

Writing is a competitive business. If you want to stand above the crowd, your writing needs to glitter brighter than a diamond at midday. To this end, a writer needs feedback on the stories they write. (I’m not talking about Aunt Rose, either).

Different avenues exist for writers—at every level—to get honest (and hopefully helpful) insight into their manuscripts. Much of this input might be available free of charge. In fact, should we ever pay for a professional edit when seeking traditional publishing?

I have seen recommendations from traditionally published authors (and even a few agents) in regards to editing. The consensus seems to be: Don’t spend money on editing your manuscript before shopping it to agents and editors. Believe me, I sighed hugely when I read this advice (since I don’t make much cash as a full-time pre-published author).

Is this the best advice for you and your manuscript?

In my sixteen-month stint as a professional writer, I’ve found feedback from a multitude of sources. Family, friends, writing groups, fellow newbie writers, published authors, and even a couple professional editors.

What a Critique Partner or Critique Group Can Do for Us

I have experienced three separate types of critiques in my writing life. My experiences may be atypical. In any case, I’ve had critiques from a writing group, a published author, and a fellow pre-published writer.

I know most writing groups are composed of pre-published authors. However, my experiences between a group setting critique and a one-to-one critique have been vastly different.

In the writing group, you have three types of people: the know-it-all, the uber-critical person, and the soft-hearted reader. Their titles are self-explanatory. None of these people will be able to help you improve your writing. In fact, they may make your story worse if you try to incorporate their advice.

If you’re a member of a critique group, you’re the person who gives honest and useful feedback on every story. You never get your feelings hurt and always balance your negative comments with positive ones. As this person, you will soon tire of receiving less-than-helpful critiques from the other members and seek feedback elsewhere.

I actually paid $50 to have a published author in my fantasy genre read the first 20 pages of my manuscript. We had a ten-minute meeting to discuss her comments. She marked my manuscript in every direction. The setting was lacking. The characters were flat. The premise sounded tired and over-used. My sentences were horribly constructed.

About ten percent of what she said helped me improve my writing. Saying what is wrong with something is not the same as offering solutions to fix the problems. In fact, I have rarely read a critique that offered helpful insight for improvement (noting all my bad habits doesn’t count, does it?).

Finally, a fellow writer offered helpful and insightful advice about the opening and characterization of the manuscript I’m currently shopping to agents. She reads the genre and has an excellent ear for strong voice and snappy dialogue. Where she excels, she gave me the best advice I’d received from all the other critiques combined.

Of course, she isn’t strong on structure or creating conflict. She knew what she liked about the characters but couldn’t tell me why she didn’t like what she didn’t like (a mouthful, I know). In short, if we struggle in the same areas, she can’t help me dig my way onto solid ground.

What Beta Readers Can Do for Us

Beta readers are readers not editors. They should not be expected to catch your grammar errors, typos, or sloppy writing. They read for content and fluidity.

Say they’re confused about why or how something happened, they make a note. If they didn’t like the characters or find them believable, they mention it. Give them a list of 23 things to comment on and you’ll get some amazing—and diverse—feedback.

I did have two fellow writers beta read my manuscript. Both of them gave insightful commentary about plot, character, setting, conflict and pacing. In most cases, every one of my six readers found different things to wonder about—which helped me plug the holes in the story.

As for helping me improve the structural flaws, there wasn’t any feedback I could use. They weren’t equipped to identify weak areas in my story or character arc.

What a Professional Editor Can Do for Us

This brings us to the woefully under-appreciated professional editor. Perhaps you have looked at these people and thought, “I can do that. What skill do they have that I don’t?” Especially since many of the best editors are also published authors.

A developmental editor will amaze you (if they’re a true professional). You won’t have to ask them about anything. They will open your manuscript and tear in.

Yes, I do mean tear into every word, sentence, paragraph, and event. Close attention will be given to the opening pages because they know these are crucial to the success of your story—both with agents, publishers, and readers.

Nothing will be off-limits. Is the setting vague? Does the character have a goal? Can the scene be easily visualized? Does the dialogue sound like something people would actually say?

Your narrative will be scrutinized. Are you using the best point of view? Are you hopping between character perspectives within the same scene? Does the description sound like something a narrator of that age would truly think?

Certainly, problems like too much telling will be addressed. However, deeper issues like the underlying structure of the story and obvious character arcs will be more important to a developmental editor.

Their job is to decide if you have a story to tell. If you do, are you telling it from the right perspective? Did you start in the best spot? Is there enough conflict to sustain tension and keep readers turning pages?

Jami is holding me to a word limit, or I could go on here for another thousand words. Bottom line: A professional editor locates the bones of your story and decides if you have a foundation. If you do, they’ll dissect the characters to help you streamline motivation. If they find inconsistencies, you will hear about it.

My Personal Conclusion

In short, I disagree with this blanket assertion: A manuscript traveling the traditional path doesn’t need an editor. I agree there are some benefits in “free” feedback, but sometimes those sources don’t push your manuscript to the top of the slush pile.

Time to face facts: You won’t hook an agent or editor with a manuscript that doesn’t shine. No matter how great your prose or how many degrees you possess, you aren’t the best critic for your written work. It’s a fact; one I was sad to encounter.

I’m a pretty effective editor, but the truth is I’m too close to my own story to recognize many of its shortcomings. The characters are my intimate friends, so I read between the lines. I see subtext that doesn’t exist. Weakness in character arc or description are the invisible woman.

So here’s my advice:

If you’ve shopped your story and no one is biting,

take the plunge to pay for editing.

Spend the money on a developmental edit to ensure your manuscript:

- has sound structure,

- has believable and relatable characters, and

- isn’t riddled with plot holes.

Look at this expense (and it isn’t cheap) as an investment in your career—like workshops, craft books and conferences. In the end, your manuscript will sparkle. You will learn how to write a stronger story and spot your weaknesses in the next manuscript. Best of all, your name will appear on the cover of the book you’ve envisioned.

*****

Sharon Hughson writes non-fiction, YA fantasy and women’s fiction. More than a decade in public education has given her special insight into the minds and voices of teenagers.

Sharon Hughson writes non-fiction, YA fantasy and women’s fiction. More than a decade in public education has given her special insight into the minds and voices of teenagers.

Reading, playing the piano and walking in the great outdoors devour her minutes (yes, only minutes!) of free time. She lives with her husband along the Columbia River in Oregon.

To learn more about her writing, visit her website.

*****

Visit Sharon’s blog to read her three-part series on her experiences with critiques. The series kicks off with a reminder that critiques often aren’t going to feel good, and we need to be prepared for that. The second post touches on the fact that when multiple feedback comments say the same thing, we should listen. And the third post explores how the ability to ask (non-defensive) questions might increase the helpfulness of the feedback (so look for that feature when searching for feedback sources).

Visit Sharon’s blog to read her three-part series on her experiences with critiques. The series kicks off with a reminder that critiques often aren’t going to feel good, and we need to be prepared for that. The second post touches on the fact that when multiple feedback comments say the same thing, we should listen. And the third post explores how the ability to ask (non-defensive) questions might increase the helpfulness of the feedback (so look for that feature when searching for feedback sources).

On her blog, Sharon goes deeper into the insights from her professional editing experience.

*****

Thank you, Sharon! Like you, I’ve heard this “don’t pay for editing before submitting” advice before, and we don’t talk enough about whether that’s still the best advice, given the changes in the industry.

As Sharon said, I don’t think authors should pay for editing right out of the gate. There are many sources for feedback, and spending money shouldn’t be our first option. In addition to what Sharon mentioned here, I’ve blogged before about my experiences with writing contests and how some of them are structured to provide feedback (although due to the contest entry fee, they aren’t technically “free” feedback).

Every agent will be different about what they can overlook. Some might be able to see past our errors or inelegant wording to the story underneath. Some might not want to help us through that weakness. Some agents consider themselves feedback agents and some don’t.

So how can we know what to do? Following the typical “don’t pay for editing” advice, the next line is often that we should shove this story under the metaphorical bed and move on to another story. For me, my second story helped me find my voice and my genre, so I understand why we might not want to stick with the same story that’s causing us problems.

But other times, we want to stick with that story and solve its problems. We might not want to give up on a story that’s the first of a series, or perhaps it’s the book of our heart. Or maybe we’re willing to invest money to speed up our learning process beyond what we could pick up on our own from free or cheaper resources. There’s no right answer for everyone and every situation.

When we don’t want to give up on a story, we might be able to use a “rule of three” to step through our revision/submission process:

- Get feedback from three free sources (beta readers, critique groups, etc.).

- Query three agents who represent our genre and accept sample pages (many agents who accept sample pages will peek at the pages even if the query is less than perfect).

- No bites? Get feedback from three more free sources and pay attention to repeating issues noted in the feedback.

- Query three more agents who represent our genre and accept sample pages.

- No bites? Pay a small amount for feedback on our opening pages or scenes (writing contests or a professional partial edit) and again pay attention to repeating issues noted in the feedback.

- Query three more agents who represent our genre and accept sample pages.

- Still no bites? Pay for a professional edit or a manuscript critique/analysis from an editor who emphasizes teaching-style feedback and specializes in our weaknesses (i.e., big picture developmental editor issues, sentence and grammar line editor issues, etc.).

If we stick to two or three feedback sources or agents on each round, we won’t burn out too many people, and we’ll still have enough feedback to look for repeating problems. That information about our weaknesses can be invaluable, as Sharon’s advice and this process are all about learning what might be holding us back.

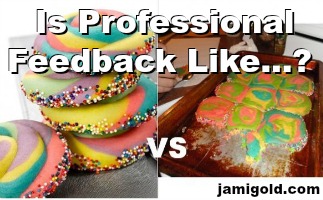

That’s my main takeaway from Sharon’s post. If we feel like something is holding us back from success (rather than just plain subjectivity) and free feedback isn’t helping us determine what that something might be, it might be worth it to invest in a more aggressive form of feedback.

When we’re feeling stuck, we want to know what’s holding us back. Sometimes, our critique partners or beta readers will be able to push us past that obstacle, and sometimes they won’t. In those cases, paying for an edit might provide the in-depth analysis that will push us to the next level for this story—and the next one. *smile*

Do you think authors pursuing the traditional publishing path should ever pay for editing? Have the changes in the industry affected your perspective on this issue? How do your experiences with the different types of feedback compare to Sharon’s? Do you think knowing our weaknesses can help us move forward with a story, or is it better to move on to a new story? When would a professional edit be a good idea or a good investment for a beginning writer?